The internet has a magical way of working: first something goes viral, then it causes outcry and in the end the coolest ones come to put things in their place.

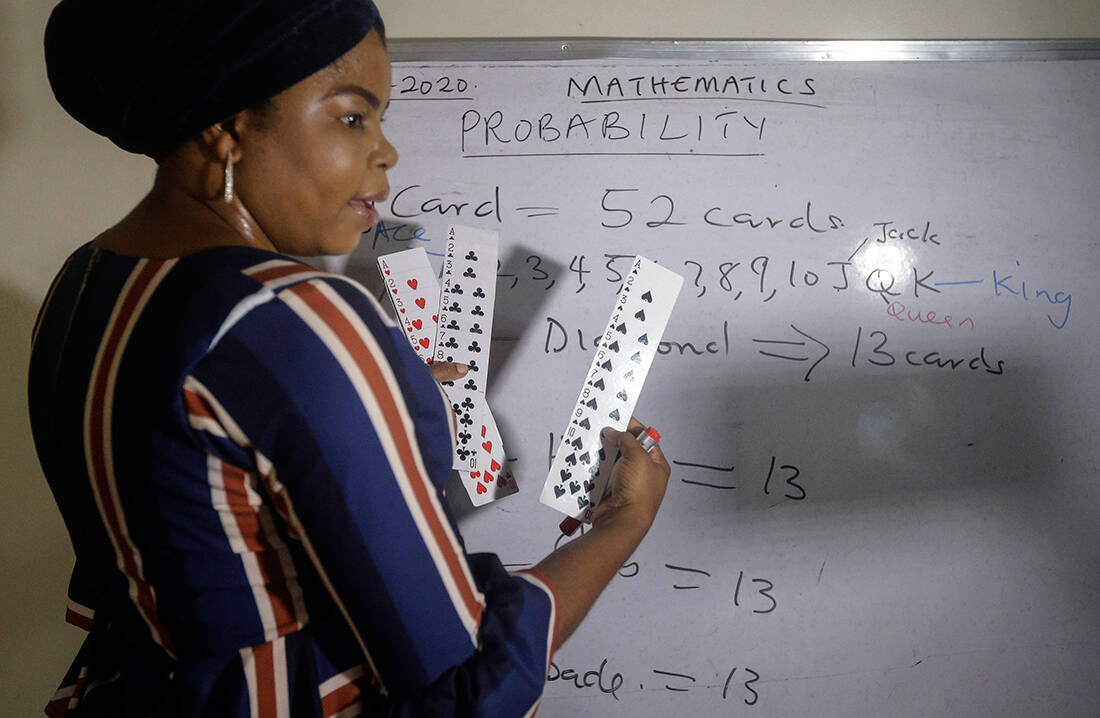

And this time something similar happened. A schoolgirl asked the timeless question in a video on TikTok, created a stir and when all this was over, it was time for the scientists to discuss it.

Congratulations on the scientific sabotage to schoolgirl Gracie Cunningham. As she applied her daily makeup while talking to the camera, she wondered if the math was true?

@ gracie.hamthis video makes sense in my head but like WHY DID WE CREATE THIS STUFF ♬ original sound - gracie

"I know they are true," he hastened to correct, "because we all learn them at school. "But who came up with the idea?" He wondered.

After imitating… Pythagoras, who lived old (without knowing exactly when), so old "that he did not even have hydraulics", then he honestly pondered where mathematics came from? Who had such a need?

The video has reached Twitter, went viral, gathered a lot and quite bitter comments and normally our story would end here. As is the case with so many things that concern the large online community.

And yet…

The conversation on social media caught the attention of Cornell professor of applied mathematics Steven Strogatz and Jordan Ellenberg, professor of mathematics at the University of Wisconsin.

Philip Goff, a professor of philosophy at Durham University in the UK, would soon join the conversation. The thing was no longer funny.

Then came mathematician Eugenia Cheng of the Art Institute of Chicago, who he also wrote a two-page answer, where he claimed that the student asked real and relentless questions about the nature of mathematics "in a deeply exploratory way".

All this is not just accidental. Unbeknownst to her, Cunningham raised an ancient, unresolved, and essential question about the philosophy of science. So what is mathematics?

Did we invent them or did we discover them? Something that introduces us to the second part of the persistent question: it is the mathematical concepts, the numbers, equations, theorems, geometric shapes, axioms, existing entities or human constructions?

On the one hand we have the thinkers who see mathematical relations as real. They are "out there" and just waiting to be discovered by man. This school of thought derives its rhetoric from Platonism.

It was the Plato one who thought that mathematical objects are abstract beings that exist in reality.

Mathematical Platonism, as it is often referred to, speaks of mathematical ideas that reside in a world of their own, not our physical world, but in a transcendental realm of unchanging perfection ("its realm is") that exists beyond space and time. .

Supporters of mathematical Platonism have been milestones in the history of science, such as Russell, Frege, and Goethe. Most recently, a strict Platonist is Sir Roger Penrose.

In the monumental "The Emperor's New Mind", he characteristically writes that it seems "there is some obvious truth in these mathematical ideas, which go beyond the mental research of a particular mathematician".

And not a few mathematicians would warmly endorse such a position. As we constantly discover new things in mathematics, it seems as if they were always there and just waiting to be seen. As eternal truths, independently and beyond us.

"I think the only way to make sense of mathematics is to believe that they are objective mathematical truths that mathematicians discover," says James Robert Brown, a distinguished professor of philosophy of science. mathematicians they are too Platonic, without always calling themselves Platonists. "

Platonism, however, is not the universal way of looking at science. If you ask other academics, or scientists in other fields, you will see that they treat Platonism with disbelief. Or at least with skepticism.

Many scientists tend to be empirical. They take on the world as things and relationships that we can experience, feel, things that we can learn more about through observation and experiment.

The idea that something is pre-eternal and exists in a sphere beyond space and time makes them feel uncomfortable. The cold empiricist will compare Platonism with the way a believer believes in the existence of God. And he will tell you later that God has been eradicated from science research for a long time.

For those who deny the eternal truth of mathematical entities, mathematics is nothing but a creation of the mind. A symbol game, better yet, awaiting proof, verification and, why not, revision.

As the mathematician Brian Davies puts it best, Platonism "has more in common with mysticism and religions than with modern science». He is not alone in this path, many mathematicians consider Platonism inherently problematic for mathematical thought.

"If the proof of the Pythagorean Theorem is valid beyond space and time", writes the professor of philosophy at City University of New York, Massimo Pigliucci, "then why not religious beliefs, such as the divine nature of Jesus Christ?".

Platonists have other philosophical challenges to overcome. If mathematical objects have their own life in other realms, then how do we get to know something about them here, in our own dimension?

The Platonists do not seem to have a convincing answer here, but people like Brown will tell you that we take mathematical truths in the same way that Galileo or Einstein conceived natural truths: intuitively. Through "mental experiments", as they are typically called.

Mental experiments, that is, conceptual constructions, that preceded the real experiments that proved their theories. Without doing anything, Galileo thought that heavy and light objects must fall at the same rate.

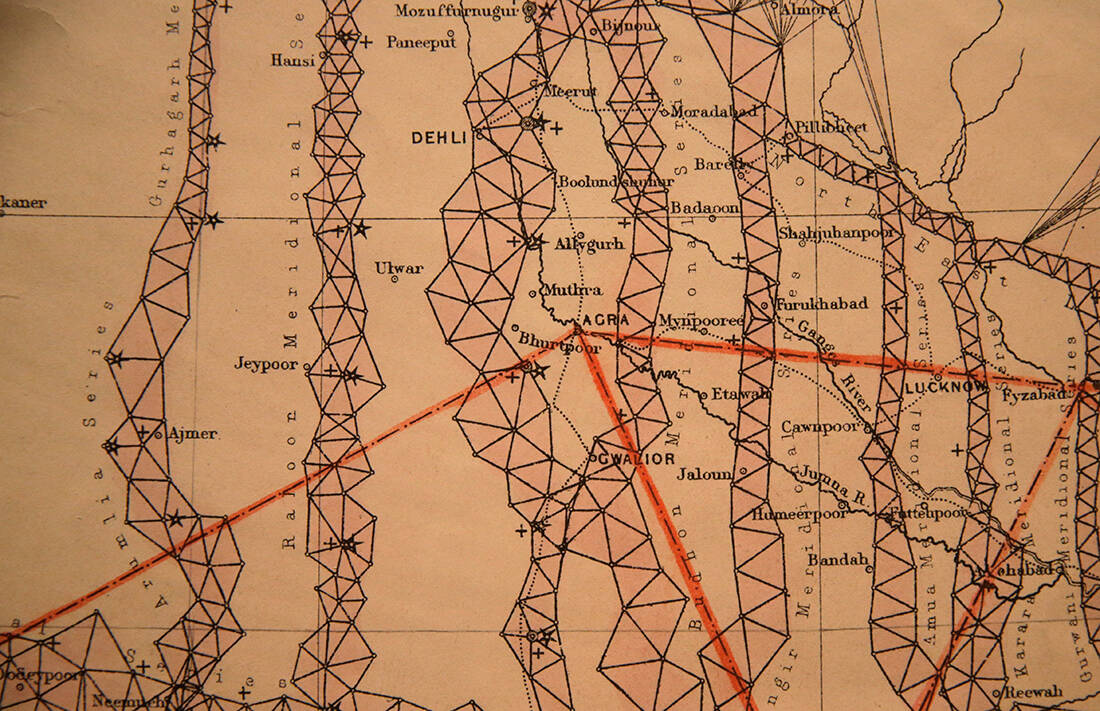

In the same way, a mathematician can prove that the sum of the angles of a triangle is 180 degrees without having to measure the angles of all the triangles. Not even a triangle. All you need is a smart mind, Brown tells us.

The discussion on the philosophy of mathematics also focuses on the very definition of abstract concepts. There are abstract concepts, the Platonist will tell you, in the same way that the natural objects of our world exist.

The axiom itself, moreover, the rational principle, is a proposition that is not proven, but is considered an obvious decision or at least the result of a methodological decision. The office is a given.

Mathematics is in this revised version of Platonism a set of rules derived from original assumptions that we have considered to be true in principle. Axioms, that is, from which other true propositions are deduced. Here, however, mathematics seems like an invention, rather than a discovery.

The extreme version of this school of thought considers mathematics as a lot chess. It is enough to write the general rules so that infinite game strategies emerge that are in line with the initial decisions.

But if mathematics is nothing more than relationships we create in our heads, why do they respond so wonderfully to the things we observe in our physical world? Why is a chain reaction in nuclear physics or a population growth model in biology perfectly represented as an exponential function?

And why is the Fibonacci sequence constantly appearing in motifs of sunflowers, snails, hurricanes, and even spiral galaxies? Why, in a nutshell, has mathematics proved so useful in describing the physical world?

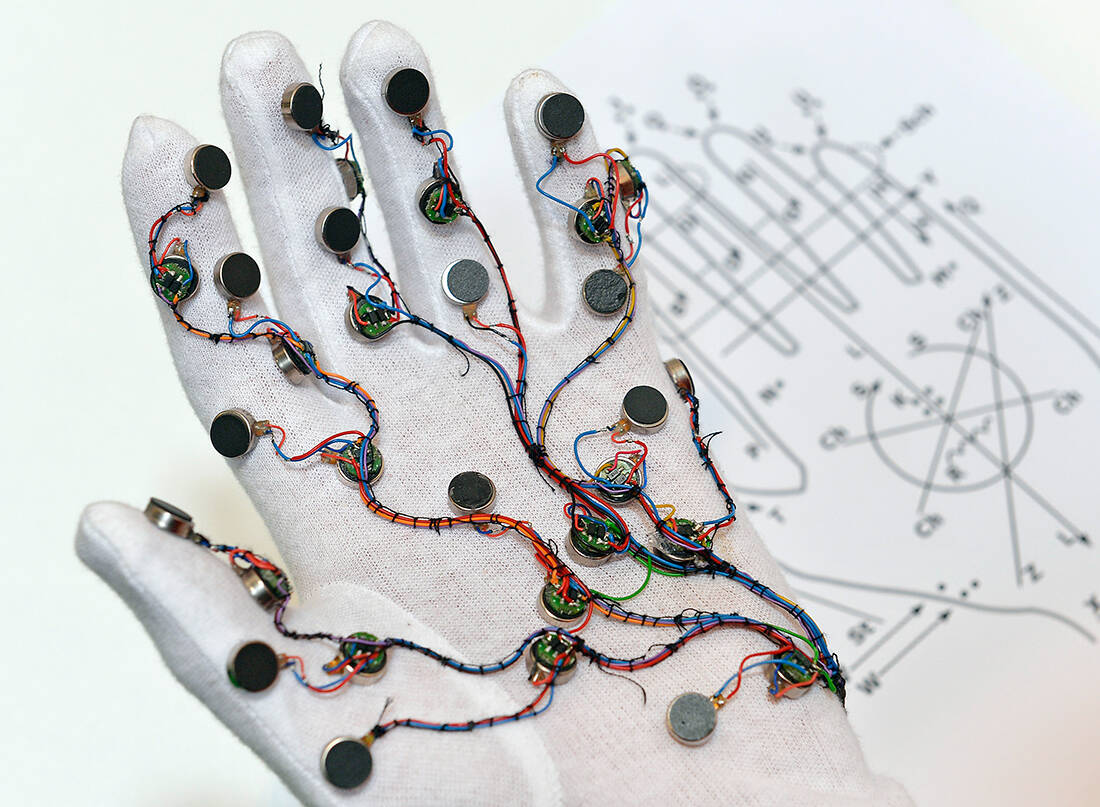

It was Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Eugene Wigner who emphasized in the 1960s this extremely practical dimension of mathematics, characteristically calling his monumental work "The absurd effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences".

The American scientist concluded that the irrational effectiveness of mathematics in solving problems of other sciences is "a wonderful gift, which we neither understand nor deserve"!

There is an answer today to the paradox of Wigner, as is often said. Mathematical axioms are not chosen at random, they answer, but they are chosen as true propositions precisely because they have to do with the way the physical world works.

"The best answer I can give to Wigner's question," Pigliucci tells us, "is that this 'irrational efficiency' is actually very logical, because mathematics is actually tied to the physical world, and so it was from principle".

They even refer to Euclidean geometry to prove their reasoning. An orderly Platonist can only claim the truths of Euclid geometry are universal and unchangeable. But we all now know that this is not the case. Its functions apply only to the given conditions of gravity of the Earth.

Even better, reaching the discussion in its juice, what are the natural numbers themselves (1, 2, 3, 4, etc.)? To most of us, and certainly to a Platonist, natural numbers look… natural. They are there and they apply whether we see them or not.

For a large portion of mathematicians, however, even these are nothing but mathematical constructions. We live in a world where we have things to count, stones, trees, people. And so we measure them. But if we lived in another natural world, say in the clouds, then the theory of fluids would be much more important for our daily lives.

The math works because that's exactly how we made it. "It's like asking why one hammer works so well in nailing. "It's because we made it for that purpose!" Pigliucci protests.

This school of thought goes so far as to see mathematics as a novel construct. Useful novel constructions. Creatures of human ingenuity are here the mathematical truths, which happen to maintain "simply" a relation to the things of our physical world.

And so in the end mathematics is just an auxiliary tool for science. And since they are made to help science, what they are doing is helping science.

There are no final answers. Nor will they likely exist in the near future. THE ανθρωπότητα he has been discussing these issues for at least 2.300 years.

The student's question was not at all naive. The questions she poses in this video, as long as she does her makeup, condense all the theoretical thinking about mathematics. Great mathematicians and great philosophers have been wondering for centuries. They just don't paint as much as they do…