For many it is a special and fascinating city, with many treasures of the past hidden in its territory, and a whole culture to remain largely buried and gradually revealed.

Under the metropolitan cathedral of his city Mexico, one of the largest and oldest in Latin America, organizes guided tours, during which visitors have the opportunity to explore the "other" temples that were discovered in the 70's but remained inaccessible to the public.

Nearly five centuries after the Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés led operations to conquer the Aztec empire for the benefit of the Crown of Castile, the remnants of the capital Tenochtitlan remain hidden a few meters below the modern Mexico City. The Spaniards began building the metropolitan cathedral in 1573 on the Aztec shrines - or Mexica, as they called themselves, "giving" the name to the country - in another move that symbolized their conquest.

When the city's electricity workers accidentally discovered a giant monolith near the temple in 1978, a five-year excavation began that brought to light the spectacular "Great Temple" of Templo Mayor of Aztecs.

This discovery, as noted by the BBC, together with the old Spanish archives for the form of the capital Tenochtitlán, gave archaeologists the possibility of concluding that there were probably other pre-Spanish buildings buried around. Thus began other excavations - some of which are in progress - to be found and other facts about the life of the Aztecs. Today, many of Mexico City's 21 million people live their daily lives just above the Aztec city waiting to be discovered.

Below the city's cathedral is Tonatiuh's Temple god of the sun. Tonatiuh was the divine ruler to whom the Aztecs referred in the "age of the fifth sun," a period predicted to end with an earthquake that would bring disaster. Piedra Chalchihuitl is a short distance away, with a "hieroglyph" written on it, which translates as "the place of the precious or the sacred".

Since 1991, the Urban Archeology Project, led by archaeologist Raúl Barrera Rodríguez, has been working tirelessly to uncover an area of 500 square meters - almost seven building blocks - in the center of Mexico City, to highlight Tenochtitlán. Today, the law requires that whenever workers repair water pipes or electrical cables underground in the city center, the National Institute of Anthropology and History be informed so that archaeologists to oversee the process.

"The law gives priority to archeology," said Dr. Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, the archaeologist who led the excavation at El Templo Mayor. While this complicates matters for workers' workshops, it ensures that whatever antiquities are found will be protected.

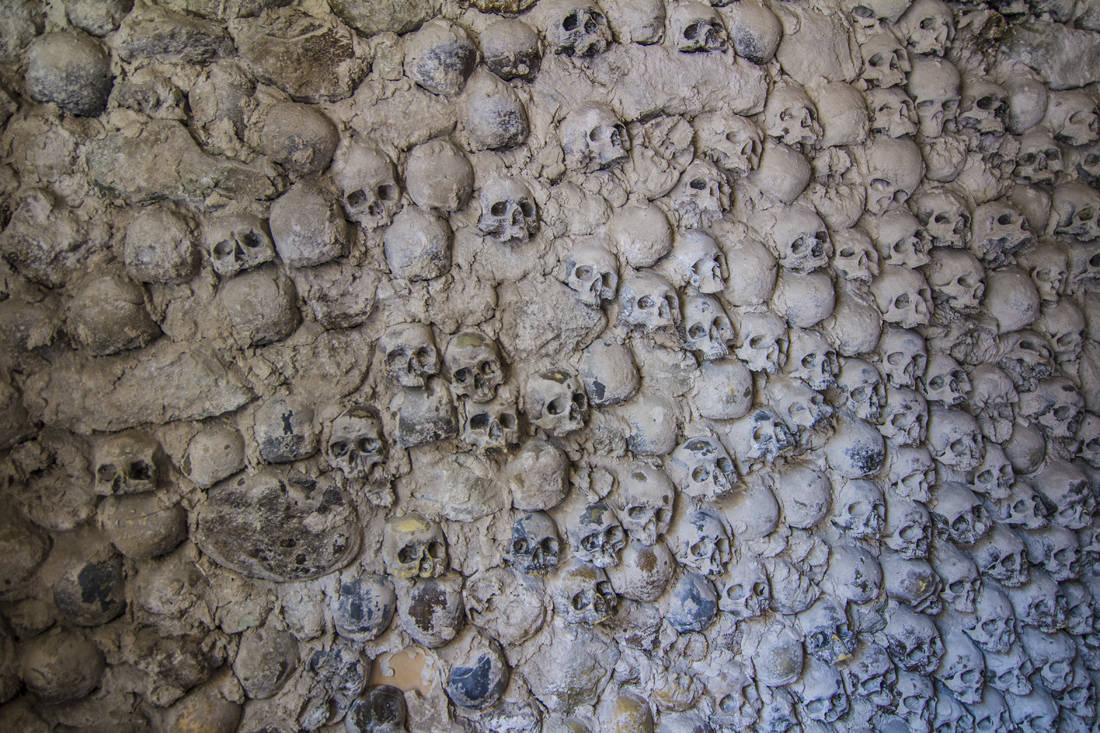

Finds in the city center do not stop coming to light. Renovation of a building behind the cathedral in 2015 led the project archaeologists to discover the "el gran tzompantli", 35 meters long, something like a "grate" with wooden pillars, where the Aztecs displayed the skulls of their victims. For two years excavations, completed in 2017, nearly 700 skulls had been discovered, along with a base with the "holes" where the stakes with skulls.

In 2017, archaeologists called in to renovate a hotel in the historic city center, discovered a stadium where the Aztecs played something like football with balls. Earlier this year, many sacrificial offerings were discovered on the steps of the Templo Mayor, including the skeleton of a boy dressed as Huitzilopochtli - god of war. Jaguar bones and layers of shells and corals have also been discovered, with archaeologists concluding that they may be near the tomb of Ahuitzotl, the Aztec emperor who ruled from 1486 to 1502.

Barrera hopes that there will be agreements with the owners of the buildings above the stadium and tzompantli so that they can come to full light and be exposed to the public soon. "In underground museums".

Similar finds are found in various sometimes unusual parts of Mexico City. By changing the metro line at Pino Suárez Station, for example, you pass through a pyramid dedicated to Ehécatl, the wind god.

Leaving the underground subway parking lot at Tlatelolco Mall, where another Mesoamerican city is located, about four miles from the historic center, there is another pyramid again in honor of Ehécatl.

Thanks to records left by the Spanish conquistadors, as well as detailed chronicles written by various Franciscan brothers and Aztec recorders, archaeologists have a fairly good picture of possible burial sites or other structures.

Very important information comes from the writings of brother Bernardino de Sahagún, in the 16th century, which described 78 temples in the center of Tenochtitlán. "What Sahagún wrote was amazing because, at the archaeological level, we were able to locate everything he was referring to," Barrera said.

However, even if we know what may be under Mexico City, excavating in such a city is not an easy task.

The Aztecs built their "urban center" on a small island in the middle of a lake. In some parts of the city, at a depth of five meters, "we find water," explains Barrera. This water-rich soil causes the city center to sink 5 to 7 centimeters a year - and in some areas even forty centimeters.

And since modern building infrastructure has been erected on various structures and areas of the Middle American era, the result is that the whole city does not sink at the same rate. After all with a simple wandering in historical Center one can see buildings leaning at different angles.

"Several years ago this problem arose," explains Matos, "the cathedral began to sink and the walls to break because there were pre-Spanish buildings below." This sign, while destructive to colonial buildings, is helpful to archaeologists as it essentially shows them where Middle American finds may be found.

"We see cracks in the buildings and we know that if we follow them, we can find a pyramid," notes Barrera. Archaeologists are following the cracks "to dig and locate the buildings that cause them," adds Matos.

However, instead of just cracking, new technologies are helping archaeologists make even more discoveries. "When we started in 1978, we used theodolites," Matos recalls, "now 3D scanners are used."

According to Barrera, they are also used radar who "read" the ground, to help archaeologists discover what may be hidden under the main streets and squares of the modern city. Of course, locating a structure is not enough, because, as he says, you may think that you have discovered something pre-Spanish and that it is ultimately a remnant of the colonial era. So again the only way to know is to roll up your sleeves and dig…

Matos also responds to those who say that digging in a modern, vibrant city, which sinks and is also seismogenic, it is probably more effort than it is worth. "They deny their own history," Matos replies, "and all these excavations have shown how similar the modern Mexico City is to Tenochtitlán."

Many of the historic buildings at the core of today's metropolis seem to serve the same functions they did 700 years ago. The cathedral is built on top of the Aztec temple, while the palace - the current presidential residence - stands on top of the ruins. of the palace of Emperor Moctezuma II, who was assassinated in the early stages of the Spanish conquest. "It's very important because it remains the point of power, from Moctezuma II to the present day, it's very symbolic," Barrera explains.

A university was built on the ruins of a Middle American school, while the Aztec city seems to have had a central square that played more or less the same role as modern-day Zócalo. "We still have the Aztecs present in our daily lives," he added.

Thus, a city founded in 1325 seems to have so much in common with today's chaotic capital. Undoubtedly the Middle American pulse is still heard below the surface of modern Mexico City, echoing the distant past, which becomes one with present.