One of the lesser known architects of our modern technological world not only envisioned a comprehensive picture of the future, but also gave us the tools to make this profound historical cut possible.

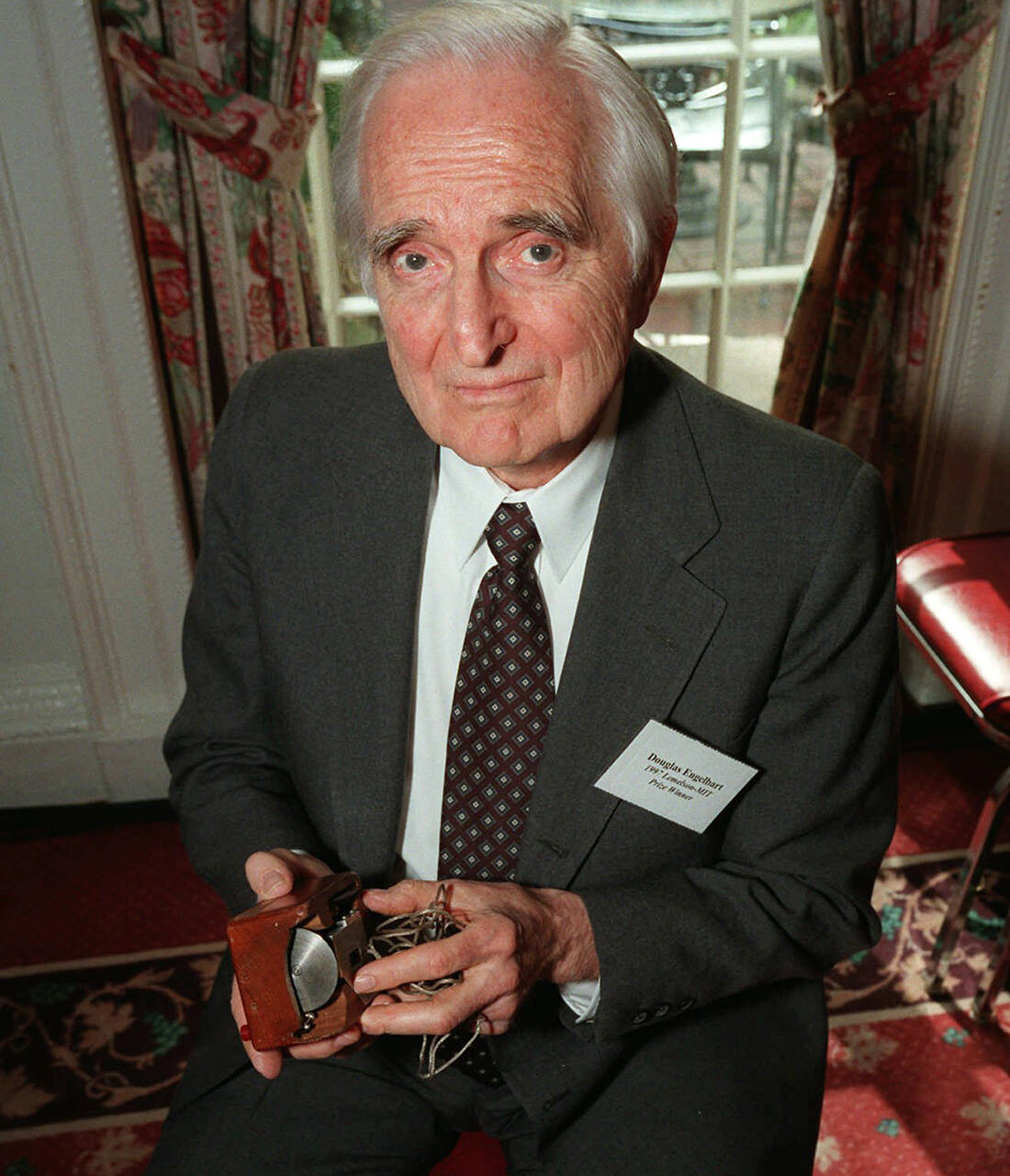

For Douglas Engelbart, history has reserved the title of "father of the mouse". Great title, alas, only for the phenomenon that Engelbart was such a thing is a little.

You see this shy engineer, who never claimed the laurels of publicity and fame, worked tirelessly to make the technological revolution possible.

The diary was written on December 9, 1968 when he appeared in front of a crowd of 1.000 in San Francisco to present his idea.

Engelbart was not, however Steve Jobs. An engineer who was used to working in the laboratory was. He did better on motorcycles than on humans. He knew neither marketing nor promotion techniques.

His purpose was to speak from the heart to other engineers, who knew the technical language to be used. And he wanted to tell them that they could use him electronic computer in new ways to solve complex problems.

This 1968 message is perhaps his greatest legacy in the world. Nothing would stay the same from that day.

Even though it remains largely unknown what exactly the "mouse father" did that winter day…

What came out of Engelbart's mouth that day in 1968 was quite revolutionary. The programmers of the day used the computer for quantitative calculations, such as census issues or banking problems.

They could also calculate the orbit of a rocket, a not inconsiderable feat.

Even in the futuristic "2001: Space Odyssey", Which had remarkably been released in the darkrooms in April of that year, the awesome (and terrifying) HAL 9000 was just an improved version of the exact same thing.

Although he could play chess and exchange jokes with the crew, his main job was to calculate numbers and run small programs. Even the sophisticated movie computer did not allow its users to write, draw or collaborate on files.

And here comes Engelbart. Who did not just think of the idea of using computers to solve the pressing and complex problems facing humanity.

But he also gave the first ever live demonstration of his vision, an interconnected computing experience that was coming to transform everything. As the "mother of all presentations" she would eventually become known, as she was indeed the forerunner of every technological presentation that would follow.

Engelbart's presentation, however, was infinitely more ambitious than any other.

When he took the stage, the timid engineer wore a microphone headset so he could talk to the rest of his team at Stanford Research Laboratory in Menlo Park, California.

Which team had laid cables along the freeway to San Francisco, connecting the two spaces that were about 50 aria kilometers apart. In fact, to project the presentation on the giant screen, they had borrowed a projector from NASA.

Engelbart began with a provocative question: "If in your office, you, an intellectual, had a computer-assisted monitor all day, and it responded instantly to your every action, how much value could you derive from it?" ».

And then he started typing, using a keyboard with numbers and numbers, instead of the traditional way of entering data with perforated cards.

The text he was writing was displayed on the screen: "Word, word, word, word". "If I make any mistakes," he stressed, "I can go back a little," proudly pointing to the new deletion function.

He then announced that he would "save" the file. "Wait a minute, I need a name," he explained, typing "Sample File." Even more revolutionary, he showed the world that he could copy the text and paste it over and over as many times as he wanted.

The magic that Engelbart did that day had no end. Now he had on his screen a list of shopping, apples, bananas, beans, soups, etc. Which he moved as if they were items up and down the list with a simple click, organizing them by item.

"There is something else I can do," he exclaimed. Display a map with the route to his house, noting a few stops. "Library," he said, "what can I do here?" Clicking on the word "library" brings up a second list. "Oh, look, overdue books." He did the same with the pharmacy.

The revolution here was not just the program, but the philosophy hidden in its heart. With the help of Bill English's assistant, Engelbart had invented a new way of using the computer, a device that as it rolled on the table moved a dot on the screen.

"I do not know why we call it ''mouse'', 'He wondered somewhat aloud,' sometimes I apologize. That's how we started it and we never changed it. " The mouse had come to stay…

Even the name given by Engelbart to his system evangelized the new. How did he say that? NLS, which meant oN-Line System! And he named it so because in addition to its specific functions, the greatest purpose of the system was cooperation between people.

And so he closed his monumental presentation, alluding to an "experimental network" that would allow all computer users to collaborate remotely.

What he described was ARPANET, a program that slowly and steadily emerged from the ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) of the US Department of Defense.

Engelbart expected that his presentation would magnetize the computer scientists of the time.

He had finally presented a complete vision for the future of computers, introducing concepts such as word processing, file sharing and a new way of handling, while integrating text, graphs and video conferencing!

The future was here with flesh and blood. Even the internet prophesied in that presentation. And so he naturally believed that the specialized audience would queue up after the end, asking him how they could work together or join his team.

On the contrary, everyone applauded him standing up and then everyone went their own way. The revolution remained on paper. At least that day, because the foundations were laid.

Although Engelbart did not wait until 1968 to unfold his dream of an interconnected world.

It is often said that the entire career of the terrific computer engineer was based on a "finding" moment he had in the spring of 1951. He had just gotten engaged and was working at NACA, NASA's predecessor, at Mountain View. California.

The 26-year-old and talented mechanical engineer had come a long way in his life from that Oregon-born county and saw his childhood plunge into the Great Depression.

Now he had a good job and the prospect of a good family. But he was not completely satisfied with them. And then came his graduation!

"It" clicked "on me," he would say years later, "in a way, you could make a significant contribution to the way people handle complexity and urgency, in a way that is universally helpful."

And so Engelbart saw the future. This thing that "clicked" him was the realization of the potential provided by technology to drastically transform the human mind.

And he "saw" in front of his eyes, people sitting behind computer screens and using words and symbols to develop their ideas. Collaboratively and collectively, always.

"If a computer could use punched cards or print on a piece of paper, then I knew it could draw or write on a screen so we could interact with the computer and do real interactive work."

And he thought that in 1951, when there were few computers in the world. Learned that the University of California (Berkeley) was preparing one, so what more natural to go there to do his doctorate.

By 1962 he had many patents with his signature. Dr. Engelbart was now working at the Stanford Research Laboratory, and that year he published his equally monumental work ("Augmenting the Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework") in which he described his vision.

At the heart of which was the central idea that the computer could maximize the human intellect. Six years before he put his dream into practice, he gave the academic community an overview of the innovative way of using the computer.

The avant-garde here was what is now commonplace. Work with data and information and then share it with a network of colleagues so they can contribute further to the project.

But why did it not have the impact it was expecting at that historic moment in 1968? As some of the attendees stated years later, who would become names in their space, the reason was simple: everyone was struck by lightning!

And when the awe passed, most people realized that all this was nice, but what did it have to do with their own work? Suppose Engelbart asked them to get rid of their daily routine with perforated cards and to open up to an unknown universe of interconnected experiences.

Until the mid-1970s, Engelbart's laboratory (Augmentation Research Center) received generous state funding to build the backbone of the ARPANET.

In a completely unorthodox move, he hired young girls who had just graduated from Stanford and even degrees in anthropology and sociology! This is because he believed that women were the only ones suitable to create a completely new culture, a new working condition.

He also had three daughters and had seen what they could do by commenting on Dad's work. "Interconnected Improved Communities" wanted to build Engelbart and now sent his assistants to workshops and institutions to help build the new world.

Of course, he faced many difficulties, insurmountable obstacles. ARPANET financiers did not understand all this and considered his efforts a failure. And so they closed the tap and his laboratory was locked.

And then he saw all these people he had been training for years moving to other research structures, like Xerox's famous lab, which stole a lot from him.

Only that all of them were nurtured by the ideas of the great visionary and whatever they did, no matter how far they went from his dream, Engelbart's basic views were always present.

He now complained that even the term "personal computer", as the computer was now advertised in the market, was a departure from the vision of teamwork.

Xerox PARC Lab led the way of evolution and everyone admitted that it was based at Engelbart's Augmentation Research Center.

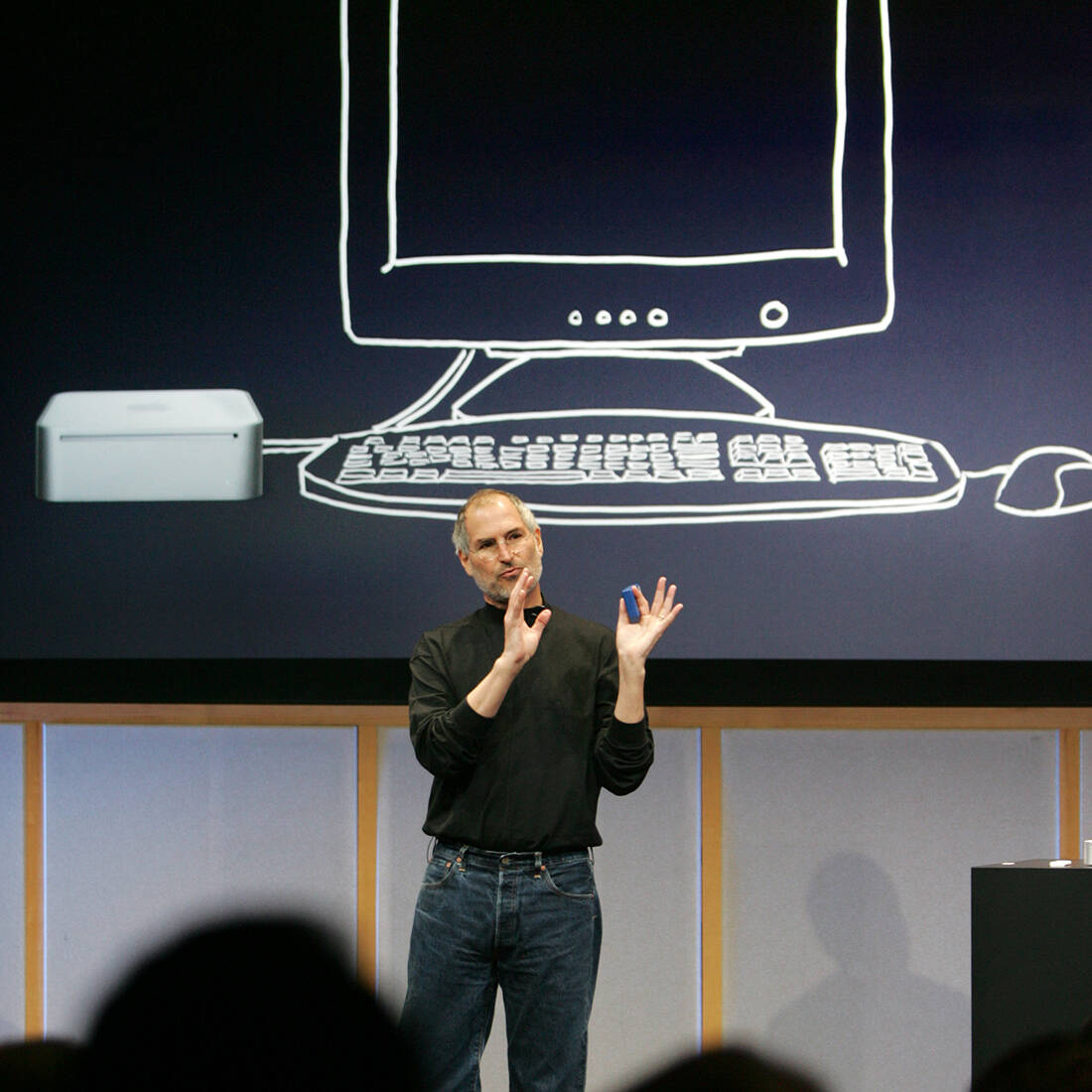

The turning point came in 1979, when Xerox allowed Steve Jobs and his team from Apple to tour its lab twice in exchange for Xerox gaining 100.000 shares in Apple.

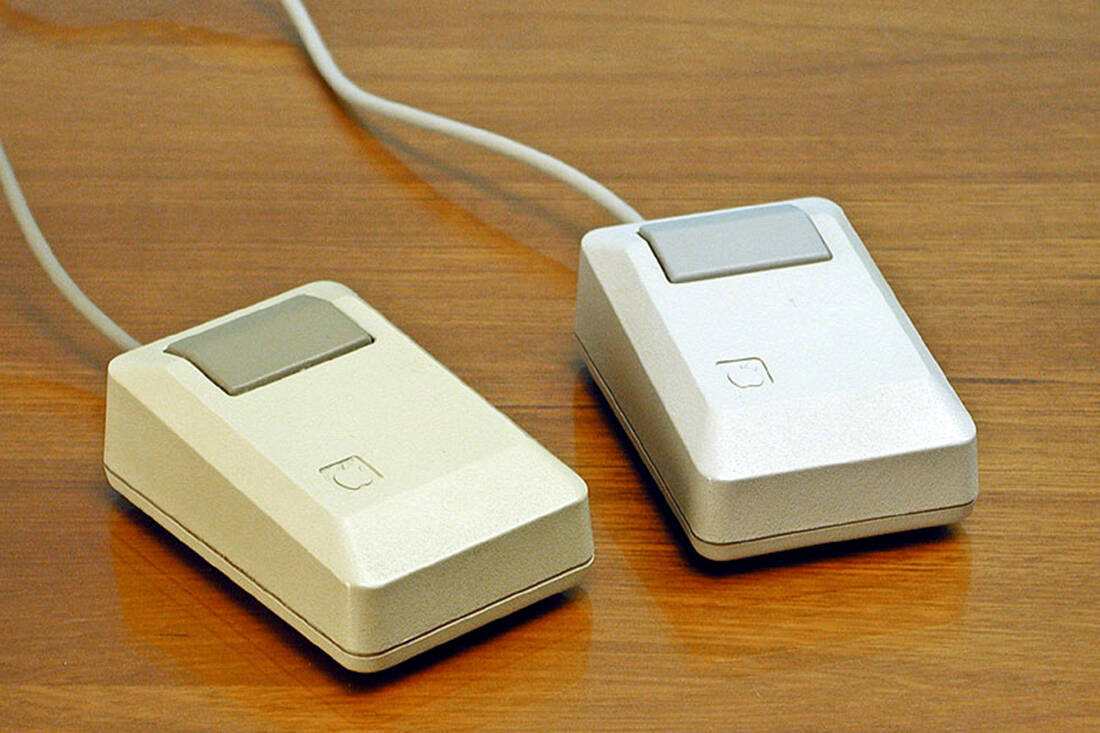

Job was fascinated by what he saw there and would incorporate much into his own vision. What caught his eye the most was Engelbart's three-button mouse, which performed different tasks each and so many more in combination.

Jobs took the rights to the mouse from the Stanford Research Institute, edited it and launched it on the market with a single button. Engelbart criticized it, calling simplification a proper abuse of his job.

Ironically enough for the career of this great visionary, the mouse was what would make Engelbart more widely known. Although it never made him rich, other than the $ 10.000 with which Stanford bought his patent rights.

He could not digest that it was the simplest and smallest element of his vision that was embraced by the entire technology industry. A vision that had everything inside, every small and big that companies like Apple Lossless Audio CODEC (ALAC), and Microsoft.

When asked in 2006 what percentage of his vision has been achieved, Engelbart replied bluntly: "2,8%".

Although he has been honored with more than 40 great awards in his career and has been an inspiration to a whole generation of young and ambitious people in the world of technology, the greatest recognition of his work was perhaps what Alan Kay, a big name and of his speech in the industry:

"I do not know what she will do Silicon Valley when it dries up at some point from Doug's ideas. "