Ο coronavirus made its appearance in China shortly before 2020 and no one could have imagined that it would become one of the great enemies of the health of the world community.

Ο COVID-19 As its scientific name suggests, it has caused thousands of deaths -mainly in China- while the list of countries with cases is growing day by day, including Greece. So far the cases are four and concern three women - one in Thessaloniki and two in Athens - and the 4-year-old child of one of them.

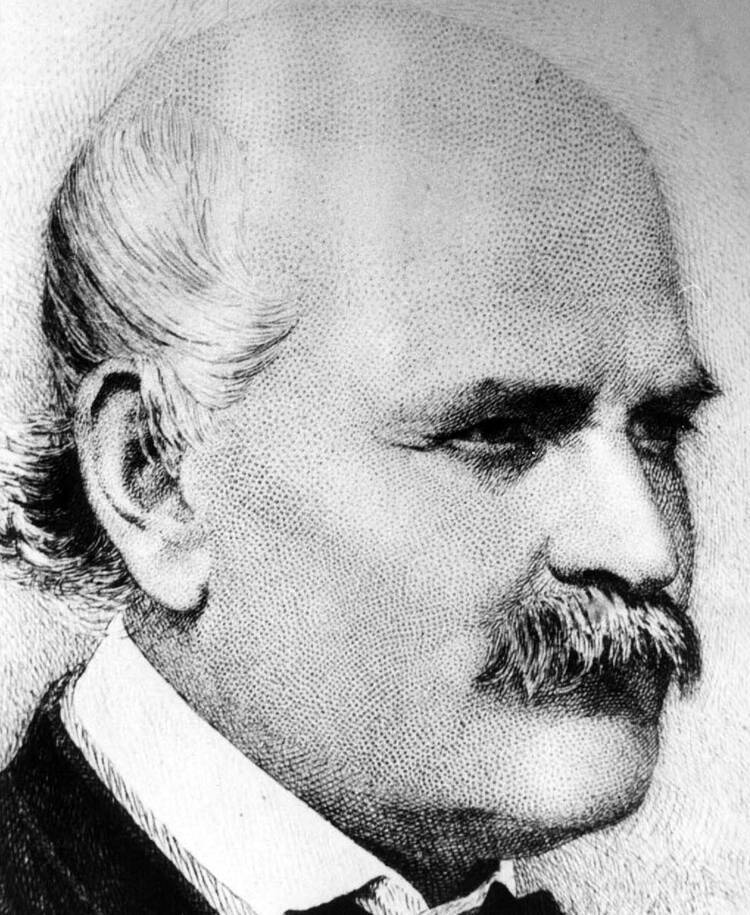

Since there is still no vaccine for the coronavirus, the medical community puts good hand washing as the most important way to deal with it. This advice, of course, goes back a long time and was inspired by the Hungarian obstetrician Ignaz Semmelweis, one of the greatest figures in medicine. The man who taught us how important it is to wash our hands managed to significantly reduce deaths, but he did not receive the due respect from his colleagues.

The end of Ignaz Semmelweis was tragic. He died in a psychiatric hospital, after being beaten mercilessly and tortured by guards. Cause of death is sepsis.

In the middle of the 19th century about 1.000 women lost their lives during childbirth as midwives. However, when doctors working in the best maternity hospitals in Europe and America gave birth, the death rate increased by 10-20%.

The cause was always postpartum fever and the last moments were tragic: fever, pus coming out of the "birth canal", abscesses in the abdomen and chest that caused terrible pain. And all this within 24 hours from the birth of the baby.

In 1846 the general medicine and surgery were the top specialties in Vienna. Semmelweis may have been a brilliant scientist, but the fact that he was Hungarian and Jewish threw him into the less brilliant field of obstetrics. But he had set a goal in his life to find the reason that 1/3 of his patients died of postpartum fever, which happened much more often when doctors gave birth and not midwives. Every day he listened to the women who took care to ask him to give them a discharge because they considered the doctors to be the harbingers of their death. Semmelweis was smart enough to listen to his patients and shed light on the mystery of death.

He eventually linked the deadly febrile fever to a type of poison carried by doctors, from autopsies performed on women's corpses, to women preparing to give birth. Today this poison is now known as the pyogenic hemolytic streptococcus of group A. As historians point out, Semmelweis was not the first doctor to make this connection. Before him, the same conclusion was reached in 1795 by Alexander Gordon and in 1843 by Oliver Wendell Holmes.

One was the obstetrician's advice to medical students and colleagues: Wash them hands with a lemon chloride solution. He even invited them to wash them for so long that there was no smell of decaying corpses from the necropsy room. Shortly after the introduction of this protocol in 1847, mortality rates in maternity wards fell sharply.

Semmelweis's ideas met with strong reactions from his colleagues as they could not accept blaming themselves for the deaths of so many women. He never agreed to publish his conclusions despite constant pressure from his supporters.

To make matters worse, he did not hesitate to become rude and insult many of the leading doctors of the Vienna hospital who had disputed his claims. These eruptions never went unnoticed by the medical community and so in 1850 Semmelweis lost his place in the hospital and left for Budapest without informing anyone.

Finally in 1861 he published his work "Die Aeriologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers" (The Etiology, the concept and the prophylaxis of childbed fever) where he explained his theories about postpartum fever and the ways in which it could be avoided. dispersing it with good hand washing, along with a series of characterizations for those who criticized it harshly.

At that time he began to suffer from depression and to distance himself more and more. He became extraordinarily rude in his social encounters and his outbursts of anger followed one another. He started drinking and spending more and more time away from his family, often having prostitutes with him.

In 1865 he was locked up in a psychiatric institution where he lived horrible moments. He was beaten several times by the guards, for many days he was tied with a scarf in a dark cell, while he was often tortured with ice water. Two weeks after his incarceration he could not stand it and died from a wound that had become infected in his hand. The autopsy showed sepsis was the cause of death.

Few attended his funeral, and there were few announcements of his death in the medical journals of Vienna and Budapest. The man who had made such a great discovery was never honored as he deserved. He was considered an eccentric figure, an unstable man who should have been removed from medicine.

However, since the early 1900s, many physicians and historians have praised his work and expressed their sorrow over his suffering. Today in every school of medicine and public health his name is spoken reverently every time the crucial subject of hand washing is taught.