In a time -even violent- controversy between the ideas of democracy and great individual wealth, lived a man who by his personal example showed a different path.

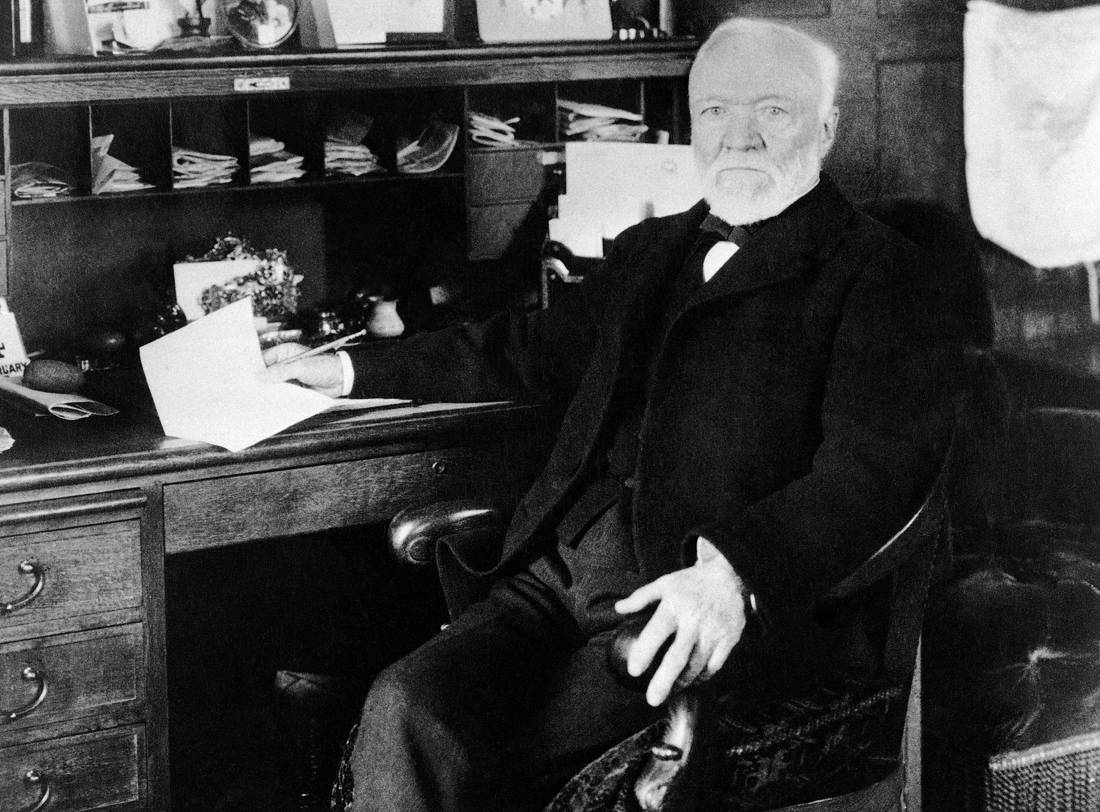

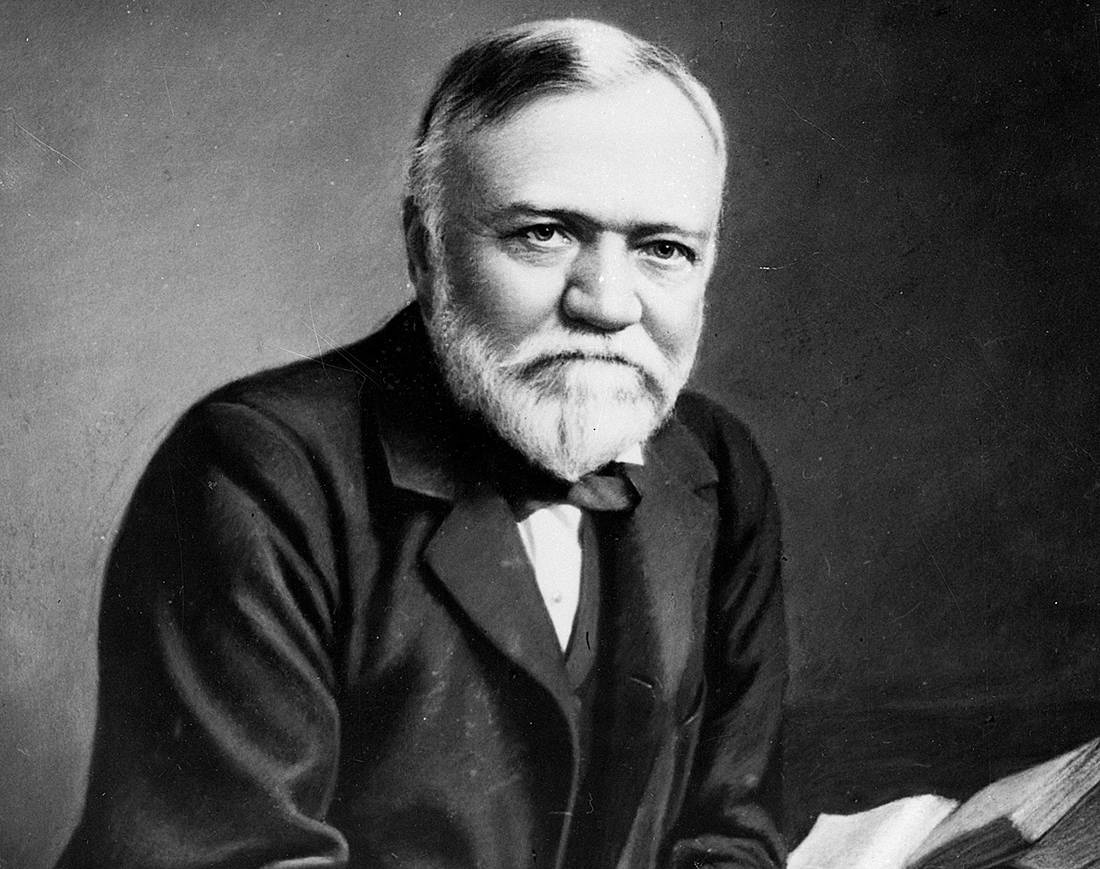

He considered himself a hero for the working people, but he crushed the unions, despite his contrary rhetoric. He was one of the most successful businessmen of his time, a generous philanthropist and benefactor, but he significantly reduced the salaries of his employees. One of the leaders of 19th century industry in America, Andrew Carnegie helped create the powerful American iron and steel industry, a process that turned a poor boy into the richest man in the world.

He wrote hundreds of speeches and articles, as well as seven books, and is perhaps best known for a series of articles published in 1889 in the North American Review, which today constitute the "Gospel of Wealth." A book in which Carnetti expresses his views on wealth, which is believed to have inspired Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. According to Carnetti, the rich should be the managers of their property, not to show it off, to offer sufficiently and not too much to their family and to use their wealth to promote the "general good". One of the phrases he loved to say, after all, was that "the man who dies rich, dies dishonored".

Shiller Robert J., a professor of economics at Yale University, noted in a 2006 article that this classic book justified the accumulation of capitalist wealth by saying that it favored philanthropy in the arts and sciences. In other words, Carnegie believed that a great deal of individual wealth led to the expansion of civilization. The "Gospel of Wealth" is based on the idea that commercial competition leads to the "survival of the fittest", with the fittest being those who have "the greatest talent in the organization".

He believed that those who excel in business and amass huge fortunes are better able to judge how the world actually works and therefore better able to judge where resources will go. Successful people are in for a rude awakening, according to Carnetti, who spends the rest of his life devoting his life to charity.

The poor boy who became a tycoon

He was born in Danfermlin, Scotland, in 1835, a difficult time for his hometown. His father was a weaver, something that young Carnegie was expected to pursue as a profession. Within a few years, however, the industrial revolution resulted in the disappearance of the weaver's profession, an art for which the area was known. Her mother's family had to work in order to support the family, opening a small grocery store and repairing shoes.

Danfermlin weavers, who were literally struggling to feed their families, turned their attention to the then-popular Hartist movement. The Chartists believed that by allowing the masses to vote and run for parliament, they could take control of the government and improve the living conditions of the working man. Carnegie's father and Tom Morrison's uncle led the Hartist movement in Danfermlin. But despite the enthusiasm of the Danfermlin Carters, the movement disappeared in 1848, when parliament rejected its demands for the last time.

"I began to learn what poverty meant," Andrew would later write. "It struck me then that my father had to apply for a job. And then I made the decision that I would cure this when I became a man. "

Fearing for her family's survival, Margaret's mother pushed the situation out of poverty in Scotland for America's many opportunities. "This country is much better for working people than the old one," said Margaret's sister, who was already living in the United States.

The Carnets auctioned off all their belongings to find that they still did not have enough money for the whole family to travel. They managed to borrow an amount and find seats on a small ship. After a difficult journey, New York finally appeared before them. The family disembarked, disoriented by the noise of the city, but anxious to continue their journey to their final destination, Pittsburgh.

By the time the Carnets arrived in 1848, Pittsburgh was already a noisy industrial city, but it had begun to pay the environmental cost of its success. "Any accurate description of Pittsburgh at the time would have been a bit of an exaggeration. The smoke penetrated and penetrated everything… If you washed your hands and face it would be just as dirty in an hour. The smoke was concentrated in the hair and skin. "And for a while, life was more or less miserable," Carnetti wrote, putting aside his usually optimistic tone. Until the turn of the century, Pittsburgh was recognized as the center of the new industrial world, boosting the American economy. And for the people who led his industries, they meant not just dirty air and water, but progress.

Father Carnegie found work in a cotton factory. Andrew got a job in the same building for $ 1,20 a week and later worked as the messaging boy at the city telegraph office. In every job he gave his best and seized every opportunity to take on new responsibilities. He learned from the outside all the streets of Pittsburgh and the names and addresses of the important people to whom he delivered his messages.

He often needed to convey messages to the theater. So he made sure to go at night to stay later and see Shakespeare and other great plays. It was the beginning of a life in the pursuit of knowledge. Carnetti also took advantage of a small library set up by a local benefactor for the working boys.

One of the people he met while working in the telegraph office was Thomas A. Scott, who was then beginning his impressive career on the Pennsylvania Railroad. Scott was impressed by the boy and referred to him as "my boy Andy", hiring him in 1953 as his personal secretary for $ 35 a month. "I could not have imagined that I could ever make so much money," Carnegie would say many years later.

Thirsty for new responsibilities and responsibilities, Carnegie went up to the Railways. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Scott was hired as military transport officer for the North and Carnegie was his right-hand man.

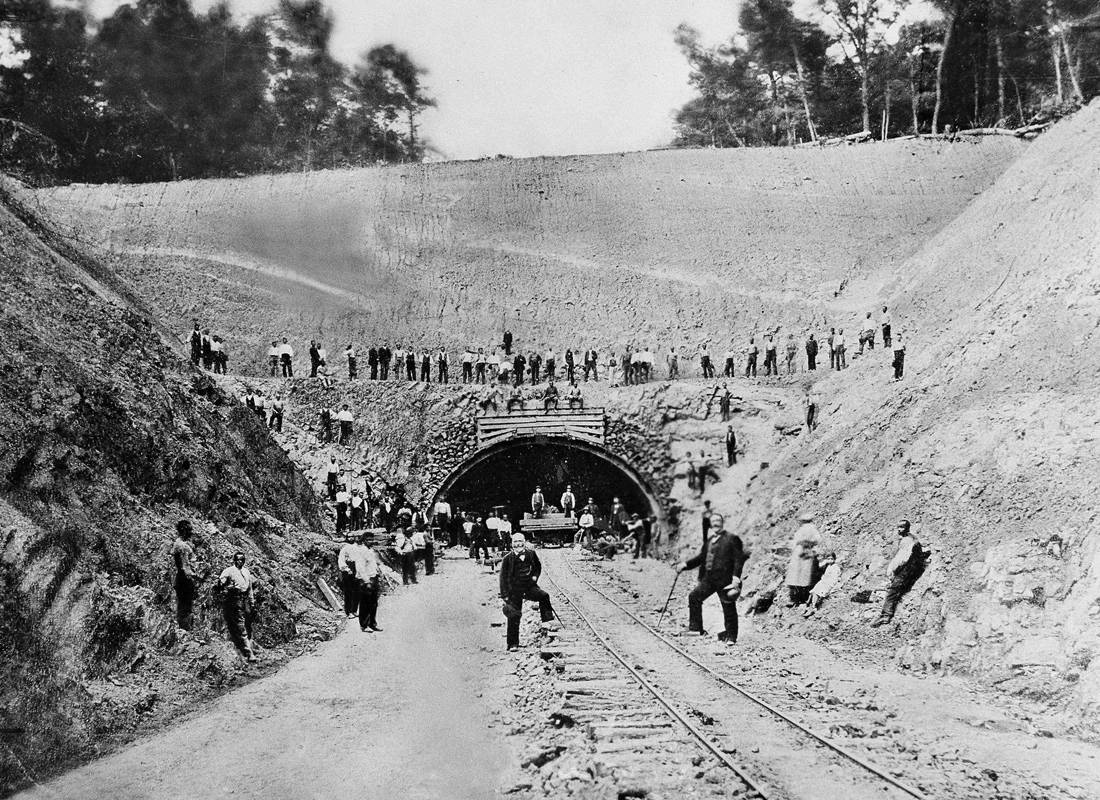

The Civil War gave impetus to the iron industry and by the end of it Carnetti saw the opportunities offered by the industry and resigned from the Railways. It was one of the many bold moves that characterized Carnetti's life in the industry and that led to the creation of his fortune. In 1865 he founded the Keystone Bridge Company and focused on replacing wooden bridges with iron ones. Within three years, his annual income was $ 50.000.

In 1868, the fortune of the then 33-year-old Carnegie amounted to $ 400.000, an amount that today translates to almost $ 5.000.000. But wealth troubled him, as did the ghosts of his past. He did not like the life of the businessman and promised that he would stop working in two years and follow a life of good deeds.

For the next 30 years, however, he would continue to make crazy money, adopting new methods in the iron and steel industry, investing in the development of the industry, and building a new factory near Pittsburgh in 1875. His main concern was to keep it low. the world, having as its motto "watch out for costs and profits will take care of themselves".

"I think Carnegie's intelligence was primarily to be able to predict how things were going to change," wrote historian John Ingram, according to PBS (Public Broadcasting System). "As soon as he saw that something was potentially beneficial for him, he was willing to invest large sums in it."

In 1880, at the age of 45, he began flirting with Lewis Whitfield, 23. His mother was the main obstacle in the relationship. Almost 70 years old, Margaret had long been accustomed to the exclusive attention of her son. The couple got engaged in 1883, but kept it a secret because of their mother. In November of that year, Margaret Carnetti died, but even then Andrew was reluctant to respect his mother. The wedding finally took place on April 22, 1887. A small, quiet, private ceremony, with just 30 guests.

Carnetti differed from other industrialists of his day in that he spoke of workers' rights to organize in unions and to protect their work. Of course, his actions did not always go hand in hand with his rhetoric. His employees often had to work long hours and at low wages. In an 1892 strike, Carnetti supported the factory manager who locked out the workers and hired criminals to intimidate the strikers. Many were killed in the controversy and it was a story that would forever tarnish his reputation and haunt him.

In his work, however, he continued unabated and until 1900 Carnegie Steel produced more steel than the whole of Britain. It was the same year that the "Moses of money" J. P. Morgan would be on his way. In 1901, Carnegie wrote the price for his business on a piece of paper and sent the offer with one of his employees to Morgan. The latter accepted it without hesitation, buying the company for 480 million dollars. Carnetti personally earned $ 250 million. "Congratulations, Mr. Carnetti," Morgan told him as soon as the deal was completed, "you are now the richest man in the world."

Wealth and charity

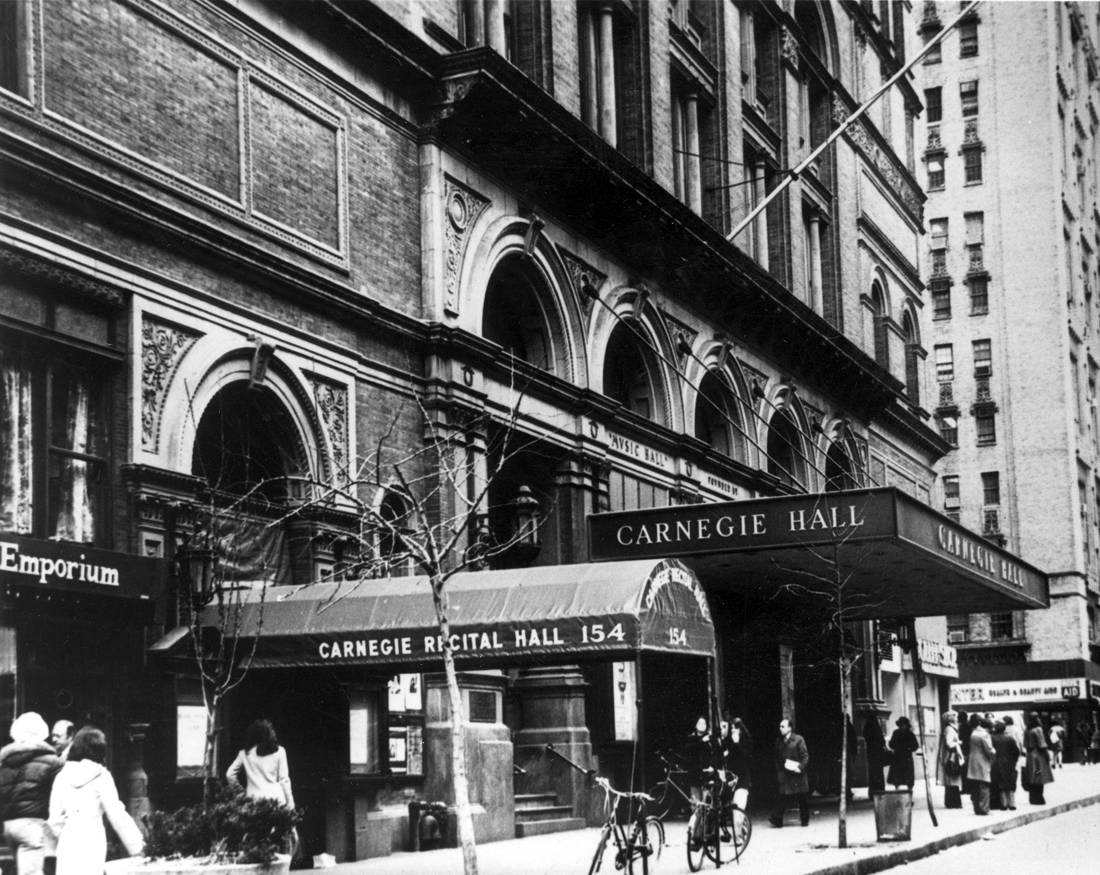

The phrase he liked to say was "the man who dies rich, dies dishonored". So Carnetti decided to turn his attention to sharing his fortune. He hated alms and chose to give his money to help others help themselves. Much of the wealth he had raised was used to build more than 2.500 public libraries, as well as to support educational institutions.

He was also one of the first to call for a "legion of nations" and a "palace of peace." His hopes for a world of peace would be dashed with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. According to Louis, with whom he had a daughter, her husband's heart was "broken" by these hostilities.

Carnetti lived another five years, but the last record in his autobiography was when the war broke out. By the time he died in 1919, he had donated $ 350 million, an amount estimated at about 90% of his fortune. Through benevolence and the pursuit of peace, he hoped that perhaps donating his fortune to good causes would alleviate the ugly details of its concentration and, in the memory of the people, he would have done the right thing. Today, however, he is remembered mainly for his generosity in the field of art and culture.