Wishma Rathnayake, a 33-year-old teacher from Sri Lanka, breathed her last in an immigration detention center in Japan, where she was being held for staying in the country while her residence permit had expired. Wishma died helpless as she was never given medical treatment while visibly ill, as described by CNN's extensive tribute to her story.

Her case made headlines in Japan and sparked debate over the treatment of foreigners in the country, where 27 detained immigrants have died since 1997, according to the Japan Refugee Advocacy Network.

Her death has highlighted the lack of transparency, in a system where people can remain confined for years without the prospect of release. A system that her sisters have launched a campaign to change.

From Sri Lanka to Japan

As a child, Wishma Rathnayake fell in love with "Oshin," a 1980s television series starring a young girl living in poverty and leading a Japanese supermarket chain.

Encouraged by her father to imitate her role model, Rathnayake began learning Japanese, dreaming of one day moving to Japan, from the small Sri Lankan town of Gampaha, northeast of Colombo.

When her father died, Rathnayake, now a university graduate, convinced her mother that she could earn enough money working abroad, as an English teacher, to finance her retirement.

Her family mortgaged her house again and in 2017 Rathnayake moved to Narita, on the outskirts of Tokyo, on a student visa.

In a tragic development, within three years, at the age of 33, she was dead.

Chasing a dream

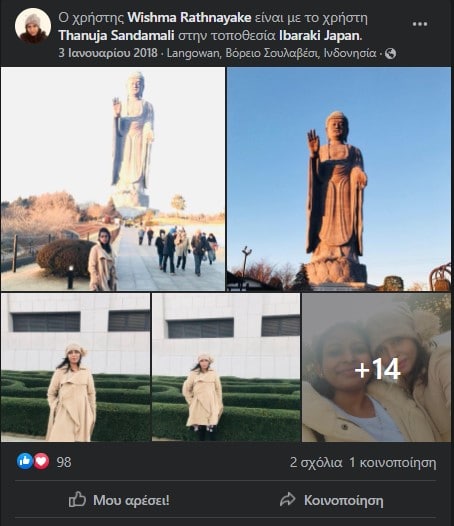

Rathnayake was 29 years old when she arrived in Narita and her posts on her Facebook profile were soon filled with pictures of tourist attractions and new friends.

Her younger sisters from Sri Lanka, Wayomi and Poornima, learned that she was taking language classes and she seemed to be happy.

"She never told us or signaled that things were not going well for her," said Wayomi Rathnayake, now 29.

What her sisters did not know was that Rathnayake stopped taking language classes in May 2018 and was later expelled.

In the same month, started working in a factory before seeking asylum in September. Her application was rejected in January 2019 and she has since been considered an illegal immigrant.

The phone calls to her house became less and less and in August 2020 it became clear why. That month, Rathnayake approached a police station in Shizuoka Province, away from home, asking for help to abandon her partner.

Rathnayake told officials her visa had expired and she wanted to go to the Nagoya Regional Immigration Office, but did not have enough money to get there, according to Yasunori Matsui, director of START, a non-profit organization that helps foreigners held in Japan.

Rathnayake initially agreed to return to Sri Lanka, but changed her mind after her partner wrote her two letters threatening to locate her and punish her if she returned home, according to Matsui.

"She thought he would kill her," said Matsui, who met Rathnayake at the immigration office in December 2020.

The first time her sisters realized she had a problem was in March 2021, when the Sri Lankan embassy in Tokyo called to tell them she was dead.

Rathnayake's family requested an exhibition and photographs, but their requests went unanswered and In May, her younger sisters traveled to Japan in search of the truth.

When they arrived, they saw Rathnayake in a coffin in Nagoya. "She seemed so different, so weak and unrecognizable. "Her skin was wrinkled like an old woman and was firmly attached to her bones," said her 27-year-old sister, Poornima.

During seven months of detention, he had lost 20 pounds.

Her sisters wanted to know why.

Above all, they wanted to see CCTV videos from the last weeks of her detention.

But authorities denied access.

A cracked system

For three months, the sisters and their legal team sought answers, met with officials and demanded the release of the video.

Their appeals were answered by supporters and some politicians who are in favor of strengthening the rights of foreign nationals in Japan, and earlier that year the decision on whether the material would be made public became the focus of debate in the country's Parliament.

At the time, Japanese lawmakers were debating a bill that would revise the rules governing the detention of foreigners, including deportation provisions, following two failed applications for refugee protection.

The purpose of the bill was to reduce the number of immigrants in Japanese detention centers, which had risen to 1.054 in 2020, according to data from the Japan Immigration Service.

However, human rights groups, including a group of United Nations experts, said elements of the bill violated international human rights standards. For example, they said the deportation clause could violate the principle of non-refoulement, forcing people to relocate to countries where they are at risk of persecution.

"The controversy over the bill has helped spark a national debate over Rathnayake's death and the issue of dealing with foreigners in Japan," said Kosuke Oie, an immigration lawyer who supports her family.

The bill was eventually repealed.

Japan has traditionally had a low immigration rate, although in recent years it has begun to accept more foreign workers.

In 2018, Japanese lawmakers approved a policy change proposed by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe that created new visa categories to allow some 340.000 foreign workers to take up high-skilled, low-wage jobs.

And in a major change last month, the Japanese government has said it is considering allowing foreigners, in some niche jobs, to stay indefinitely, starting in 2022.

However, some say Japan still has a long way to go and that Rathnayake's death is shedding light on an immigration system in urgent need of reform.

Sanae Fujita, a researcher at the University of Essex Law School, says the main problem is that Japan's immigration office has a lot of power and is not accountable to anyone.

"Unlike other countries, in Japan the immigration process is handled exclusively by the immigration service - there is no court involvement," she said. "This lack of judicial control results in what some have called a 'black box' of the process, without any oversight."

In 2019, Human Rights Now called for a ban on arbitrary detention in Japanese immigration structures and related legal reforms, following a hunger strike by 198 detainees in such structures.

In a statement, the rights group said that detention facilities should be used as a "last resort to reduce their overuse".

Fujita claims that Rathnayake's death could have been avoided if the Japanese government had listened to the United Nations's human rights recommendations to Japan. These included the imposition of a maximum detention period and the possibility for detainees to request an independent review of their case.

A spokesman for the Immigration Service declined to comment on Fujita's allegations.

"They treated her like an animal"

In August, a report by the Japan Immigration Service, involving independent experts, including medical professionals, found that the Nagoya Regional Immigration Bureau had neglected to provide Rathnayake with adequate medical care.

Officers and supervisors of the unit were reprimanded and the Japanese Minister of Justice and Head of the Immigration Service formally apologized for her death.

For the first time in the event of an immigrant death, Japanese officials have allowed the Rathnayake sisters to watch a montage of two hours showing the last two weeks of her detention. They could only watch half of it.

Poornima Rathnayake said the video made her sick.

Wayomi Rathnayake told reporters shortly after the screening that the excerpts showed her sister falling out of bed and the guards laughing as milk ran from her nostrils.

"In the video, the guards told Wishma to get up on her own. Her repeated calls for help went unanswered, as the guards urged her to get back on her bed alone. "She tried to get their attention, but they ignored her," Wayomi Rathnayake told CNN.

Some sections were mounted, suggesting that officials were hiding the truth, he said.

"What I saw in the excerpts upset me so much that I felt that there were others much worse."

The sisters finally saw larger excerpts from an edited video in October.

The staff seemed to be trying to feed Rathnayake, even though she could not keep anything inside. And the day before her death, staff did not call an ambulance, even when she did not answer their calls, said Oie, the family's lawyer.

Refusal of treatment

The Immigration Service report found that Rathnayake had been complaining of stomach aches and other symptoms for months before her death.

The report states that he underwent medical examinations such as urine tests, blood tests and chest x-rays to determine the cause of the problem.

However, on the day she died, facility staff were late to call emergency services, even when her condition appeared to be deteriorating.

The report states that in the months before her death, Rathnayake worked with immigration authorities, but her behavior changed when she decided she wanted to stay in Japan.

The report claims that its supporters had said it would be more likely to be released on parole if she was ill - a claim disputed by Matsui's lawyer. Temporary release allows detainees to live in the community while awaiting deportation.

www.ertnews.gr